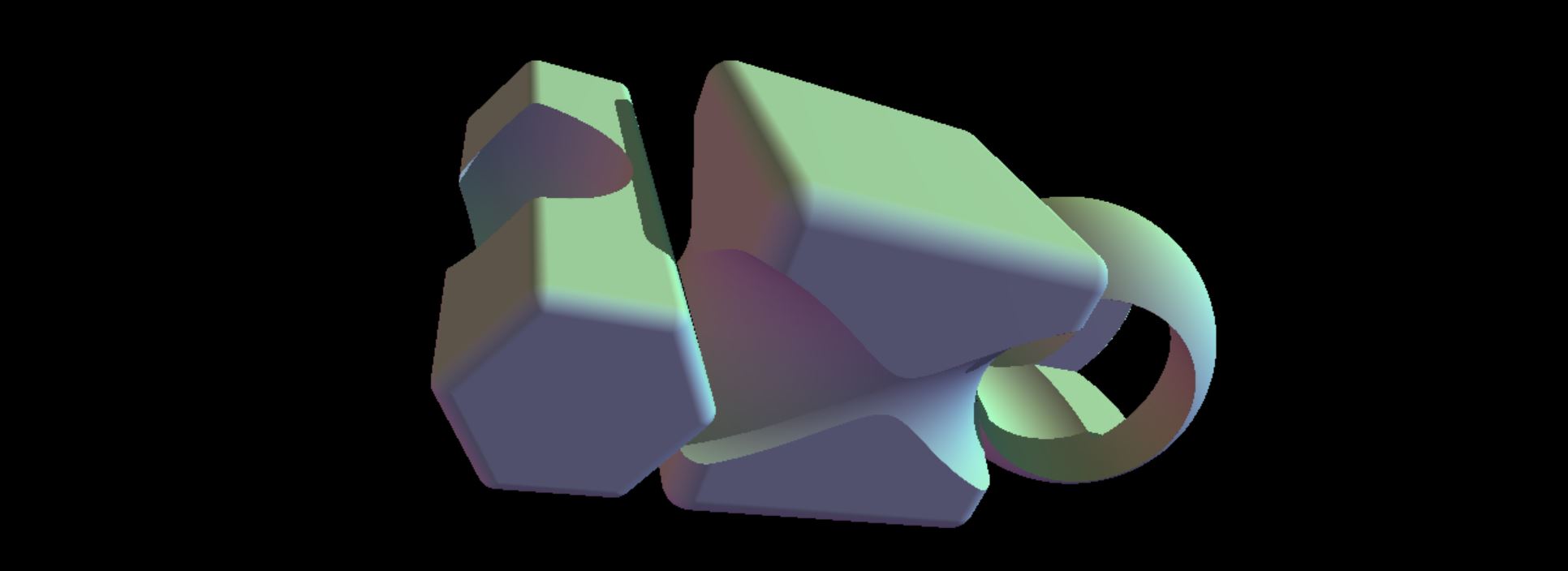

Rendering Signed distance functions, C++20 modules, no virtual stuff

Hello Signed Distance Functions

As mentioned in the previous post, I’ve implemented a little SDF (signed distance field) shape rendering library using some new(er) features of c++20. I’m gonna walk through some of the decisions I made for this one, as there are a lot of decisions I made along the way that were a bit outside of my comfort zone.

SDF refresher

We have shapes, which define a simple math function that reports either the distance to a surface, or a bound on that distance. To render this, we march along rays from the camera origin until we hit a surface - a hit exists where SDF(shape, testPointOnRay) is near 0.

These shapes can be combined via intersection, subtraction, and simple union. they can also be modified by operations like smoothing or various transforms. A composite SDF object could be described by a tree, eg. BinaryOp(intersection, round(box(…), cone(…)).

So! the overall structure of this little experiment is to produce a tree structure that supports combining these elements, and traversing them to determine the distance from a test point in 3D space to the surface of the compound object.

I’ve written (and so have you, probably) recursive tree data structures before:

template

// the items then would be our SDF shapes / binary ops, something like this: class AbstractSdfShape { virtual float distanceTo(vec<float,3>& pnt)=0; //… more virtual methods, depending on what we want to do. }; This is a pretty straightforward approach, with some benefits and some downsides. on first glance, its short, and you can use a pointer to a base class as T to get runtime polymorphism for the items at hand. As a downside however, its easy to create a tree in which you could have a binary op (lets say - subtract) with more or less than 2 children, which to me seems ill-formed. also, all your polymorphism is done via a virtual interface, which I’m not opposed to in general, (and compilers now de-virtualize things?) but still I’d like to try an approach with some other goals in mind:

- I’d prefer to not have to alter the interface of the SDF shapes to add new functionality.

- runtime polymorphism is a must, however I’d like to try to avoid virtual interfaces, purely as an exercise in exploring alternatives.

- I’d like this to be fairly easy to add both new functionality, and new shapes / sdf operations.

- I’d like it to be impossible (compile time error) to produce ill-formed trees, but also it seems important to me to keep the math-y parts somewhat separate from the tree parts…

- I’d like the code to be fairly compact.

With those goals in mind - I’ve gone with std::variant as my pointer-to-base-class alternative. How does it work? well it works a lot like the V-table in a virtual class, except its not built into the language. There are reports that as a result, it can be a bit slow, depending on how many potential values are stored in the variant. With all the above in mind, lets take a look at what I actually created. All the code is on github, and before we dive in, I’ll explain some other choices I made:

- C++20 modules! This is one of my favorite new features of c++, so of course I had to try it out. As far as I can tell, its working great!

- Visual Studio 2022 & Windows 10 - yup, this is my comfort zone. I’ve made a very sloppy OpenGL Win32 app, purely as a playground for these ideas. I should mention also that VS2022 has really great support for C++20.

- Im using my own immutable vec3 library as a submodule, as well as the brilliant IMGUI. Ok sidebar over, on to the code!

The SDF / Math part

// SDFBOX.IXX

module;

// we use macros in .ixx modules to privately conjoin some compile-time strings

// anything included or #defined between 'module' and 'export module sdfBox'

// will not leak to our importers!

#define UI_NAME "box"

#include "guiDef.h"

#include <string>

#define SNAME UI_NAME

#define SDEF "struct " SNAME " {vec3 dim;};"

#define FNAME "sdfBox"

#define FNBODY R"(

vec3 d = abs(p)-self.dim;

vec3 z = vec3(0,0,0);

vec3 m = min(d,z);

return length(max(d,z)) + max(m.x,max(m.y,m.z));)"

#define FNDEF decl_glslFunc(FNAME,SNAME,FNBODY);

So the first the we can see is a bunch of old-school preprocessor stuff in the global module fragment of our file, which is a module file. stuff here wont leak to our importers, which is nice! This section above includes a .h file full of macros, as well as some conjoined strings which form a little GLSL snippet that would evaluate this SDF of a box in that language.

export module sdfBox;

import imvec;

import string_helpers;

export namespace SDF {

using namespace ivec;

template <typename F>

struct box {

ivec::vec<F, 3> dim;

box() : dim(vec<F, 3>(1, 1, 1)) {}

box(vec<F, 3> size) : dim(size) {}

};

template <typename F>

F distanceTo(const box<F>& self, const vec<F, 3>& p) {

vec<F, 3> d = p.abs() - self.dim;

vec<F, 3> z(0, 0, 0);

return d.max(z).length() + d.min(z).maxComponent();

}

The above section exports a very simple struct box, which is defined by its size in X, Y, and Z. After that is a free function distanceTo which evaluates the signed distance between its first argument (a box) and a test point p. very straightforward! All SDF shapes must have a distanceTo function defined for them, with a similar signature. C++ will then very helpfully figure out which one to call via overload resolution - a brilliant form of static polymorphism.

decl_uiName(box, UI_NAME)

decl_glslInterface(box, SNAME, SDEF, FNAME, FNDEF)

export template <typename F>

std::string glslLiteral(const box<F>& self) {

return std::string(SNAME) + "(" + vecLiteral<F, 3>(self.dim) + ")";

}

};

The final section above declares some more free functions, which support other parts of the interface - specifically a function which just return the UI name of this type “box” and the GLSL interface, which is used when we traverse a tree of these objects to generate a GLSL shader that would render that object. I find it nice that the GLSL definition is right next to the C++ equivalent, but of course these could be defined anywhere that makes you happy. Do note that decl_uiName() and decl_glslInterface() are macros defined in guiDef.h, and they hide the boilerplate of these repetitive free functions without polluting the global namespace. Lastly, glslLiteral() returns a non-compile-time string that would construct a box with a literal vec3 in GLSL.

box.ixx is of course a module that defines the signed distance function to a box in 3D - lets take a look at a different SDF class:

// UNION.IXX

module;

#include <string>

#define max(a,b) a > b ? a : b

#define min(a,b) a < b ? a : b

#include "guiDef.h"

// "empty" is a magic word that lets our shader-builder visitor know its

// safe to omit this parameter from the generated GLSL function 'sdfUnion'

#define sName "empty"

#define sDef ""

#define fnName "sdfUnion"

#define fnDef "float " fnName "(float a, float b) { return min(a, b); }"

export module sdfUnion;

import imvec;

import string_helpers;

export namespace SDF {

// 'union' is of course a keyword - blerg

template <typename F>

struct union_sdf {

// intentionally empty!

};

Union is the simplest binary SDF operator - simply returning the minimum distance between its two arguments. Like sdfBox, we must have a struct union_sdf even though its empty! this is because we’re relying on overload resolution to figure out what binary op to call! sdfBinaryOp is the meat here - we could have called it distanceTo, but it felt nicer to differentiate between shapes and binary operations on shapes with a name, even though they have a different signature.

template <typename F>

inline F sdfBinaryOp(const union_sdf<F>& i, F a, F b) {

return min(a, b);

}

decl_uiName(union_sdf, "union");

decl_glslInterface(union_sdf, sName, sDef, fnName, fnDef)

export template <typename F>

std::string glslLiteral(const union_sdf<F>& self) {

return std::string("");

}

}

The Tree part

So We’ve seen two classes SDF functionality - a simple shape and the simplest binary operator. They all have an interface made of free functions, and our method of polymorphism is function overload resolution. We’re going to combine them using trees (for an example a binOp like union would have two children, while a shape like box must have none). There are at least 4 classes of these SDF operations, and it is a goal to allow a user of this library to add more with little effort:

- Shapes like box, torus, sphere, etc.

- binary operators (union, intersection, subtraction)

- unary operators like round, shell, etc.

- domain operators, like translate, rotate, repeat, etc.

Each of the above classes has a distance function with a slightly different signature:

- Shapes: F distanceTo(shape, point)

- binary operators: F sdfBinaryOp(operatorData, dstA, dstB) //sometimes operator data is empty

- unary operators: F sdfUnaryOp(operatorData, dstA)

- domain operators: vec<F,3> transformDomain(operatorData, point P)

Each of these signatures returns a distance, except for the domain operators, which fiddle with the test point. We can see also from this that we will need two layers of polymorphism - one abstracting the 4 classes above, and one for each of the 4 classes, each abstracting the different, specific shapes or operators in that class. In classic form, it might look like so:

class INode {

//tree stuff

};

class IShapeNode: public INode {

virtual distanceTo(...)=0;

};

class IDomainNode: public INode {

virtual transformDomain(...)=0;

};

class IBinaryNode: public INode {

virtual sdfBinaryOp(...)=0;

};

class IUnaryNode: public INode {

virtual sdfUnaryOp(...)=0;

};

However as allready states, we’ll be givving std::variant a spin! Hang on because this is where it gets confusing!

/// SDFNODE.IXX

#include <variant>

export template <class... nodeVariants>

class StructuredTree {

protected:

explicit StructuredTree() = delete; // non-constructable class...

public:

using NodeVariant = std::variant<nodeVariants...>;

};

export template <class Var>

class Node {

protected:

Var payload;

template <typename V> // todo require V to be assignable to Var

Node(V&& v) : payload(std::move(v)) {}

public:

inline Var getPayload() const { return payload; }

inline void setPayload(Var p) { payload = p; }

//~Node() = default;

};

Ok, we’ve got a template parameter pack… and a Node class that is just a wrapper for its payload of type Var.

Whats going on here? The template parameter pack is just immediately fed to a type alias using NodeVariant = std::variant

export template <class P, class GroupType>

class BinOp : public Node<P> {

protected:

std::vector<typename GroupType::NodeVariant> children;

public:

// getters, etc... missing for brevity

};

Ok here we can start to see whats going on - because this is a recursive type, we need a symbol to define the type of any possible node, which is tricky because we’re currently in the middle of defining a class of BinaryOp, and we haven’t even seen the others yet, nor forward declared them. We solve this by the template parameter GroupType, which is a stand-in for StructuredTree (you can see we refer to its sub-type here): std::vector<typename GroupType::NodeVariant> children;

However StructuredTree is itself templated, and its template argument pack must be the list of all the classes of SDF nodes! This somewhat circular template :sparkles: is often referred to as CRTP.

Another point of note is the use of std::vector for storing children tree-nodes. Because GroupType::NodeVariant is incomplete, we need a container that can handle that - we could have also used a smart pointer - it really isn’t important, and we could of course change it at any time. Lets proceed to Unary ops, Domain Ops, and Shape (leaf) nodes:

export template <class P, class GroupType>

class UnOp : public Node<P> {

protected:

std::vector<typename GroupType::NodeVariant> child;

public:

template <typename V>

explicit UnOp(V&& v, typename GroupType::NodeVariant&& subTree) : Node<P>(std::move(v)), child({ subTree }) {}

inline const typename GroupType::NodeVariant& getChild() const { return child[0]; }

inline typename GroupType::NodeVariant& getChild() { return child[0]; }

inline typename GroupType::NodeVariant&& takeChild() { return std::move(child[0]); }

inline void setChild(typename GroupType::NodeVariant&& node) {

child[0] = std::move(node);

}

};

export template <class P, class GroupType>

class DomOp : public Node<P> {

protected:

std::vector<typename GroupType::NodeVariant> child;

public:

template <typename V>

explicit DomOp(V&& v, typename GroupType::NodeVariant&& subTree) : Node<P>(std::move(v)), child({ subTree }) {}

inline const typename GroupType::NodeVariant& getChild() const { return child[0]; }

inline typename GroupType::NodeVariant& getChild() { return child[0]; }

inline typename GroupType::NodeVariant&& takeChild() { return std::move(child[0]); }

inline void setChild(typename GroupType::NodeVariant&& node) {

child[0] = std::move(node);

}

};

export template <class P>

class LeafOp : public Node<P> {

protected:

public:

template <typename V>

explicit LeafOp(V&& v) : Node<P>(std::move(v)) {}

};

As you can see above, the pattern is much the same - each of the classes of node type has storage for children (except for the leaves aka shapes) and all of them have a template placeholder for the type of any node, as well as a template for the possible payloads. We do extend Node as a way of storing the payload, but nothing is virtual.

In the next section, we wrap everything up by extending StructuredTree<…> thereby fulfilling the GroupType we pretended would exist above. We also make ‘nice’ type aliases for our various classes so we can maybe type less in the future. We leave ourselves room for extensibility by not yet defining all the binop/unaryOp/shape payloads, and by leaving in a final …OtherNodeClasses placeholder, for further extensibility.

export template <typename B, typename U, typename D, typename L, typename... OtherNodeClasses>

class sdfTreeGroup : public StructuredTree<

BinOp<B, sdfTreeGroup<B,U,D,L,OtherNodeClasses...>>,

UnOp<U, sdfTreeGroup<B, U, D, L, OtherNodeClasses...>>,

DomOp<D, sdfTreeGroup<B, U, D, L, OtherNodeClasses...>>,

LeafOp<L>,

OtherNodeClasses...> {

public:

// variants of payload, per node-class

using binVaraints = B;

using unaryVariants = U;

using domainVariants = D;

using leafVariants = L;

// node-classes

using BinaryOp = BinOp<B, sdfTreeGroup<B, U, D, L, OtherNodeClasses...>>;

using UnaryOp= UnOp<U, sdfTreeGroup<B, U, D, L, OtherNodeClasses...>>;

using DomainOp = DomOp<D, sdfTreeGroup<B, U, D, L, OtherNodeClasses...>>;

using Shape = LeafOp<L>;

};

Ok - the last part ties the generic stuff into an ‘implementation’ of this library:

template <typename F>

using binOpVariant = std::variant<union_sdf<F>, smoothUnion<F>, intersect<F>, smoothIntersect<F>, subtract<F>, smoothSubtract<F>>;

template <typename F>

using unaryOpVariant = std::variant<round<F>>;

template <typename F>

using domainOpVariant = std::variant<move<F>, repeat<F>>;

template <typename F>

using shapeVariant = std::variant<cone<F>, box<F>, torus<F>, sphere<F>,capsule<F>,hexPrism<F>,cylinder<F>>;

using sdfNode = sdfTreeGroup<binOpVariant<float>, unaryOpVariant<float>, domainOpVariant<float>, shapeVariant<float>>;

SO - finally, we have the type of the tree - sdfNode! its got all the known payload types baked, in, and its pretty easy to add more!

But… this seems very confusing! Why did we do this again?

Yes. I wont lie, this took me quite some time to write, and the error messages are not friendly! Its probably not more performant than a virtual interface, and that form will be much more familiar to many readers, which is no small benefit! What did we get for all this generic gibberish?

- Its very loose coupling! The distance functions, the GLSL generation, all of it is free-function based! The tree stuff knows NOTHING of the math stuff, and vice-versa! This can make modification down the road very easy to isolate.

- Compile errors - you will get them, but they can be quite unclear. I considered adding c++20 Concepts to the template parameters, however that did not improve the situation much - I dont think the VS2022 messages for these are finished baking.

- Nothing is virtual - not a big win, and we still pay something for the runtime-polymorphism as we will see, but at least our objects pack well and there is minimal indirection.

The Visitors

Its hard to evalute this setup without looking at the actual use cases of these SDF trees. Because of the recursive stucture and decoupled interface, a visitor pattern makes clear sense. I’ve implemented a GUI visitor, which lets IMGui manipulate a tree, a GLSL shader generator visitor, and of course a distance visitor.

///DistanceVisitor.ixx

export template<typename F, typename GroupType>

F visitDistance(const typename GroupType::BinaryOp& node, const ivec::vec<F, 3>& p) {

// visit children first

F a = visitDistance<F, GroupType>(node.getLhs(), p);

F b = visitDistance<F, GroupType>(node.getRhs(), p);

return std::visit(

[a, b](const auto& arg) {return sdfBinaryOp<F>(arg, a, b); }, node.getPayload());

}

export template<typename F, typename GroupType>

F visitDistance(const typename GroupType::Shape& node, const ivec::vec<F, 3>& p) {

return std::visit( // deduces arg-type for every variant of shape payload

[&p](const auto& arg) {return distanceTo<F>(arg, p); }, node.getPayload());

}

export template<typename F, typename GroupType>

F visitDistance(const typename GroupType::UnaryOp& node, const ivec::vec<F, 3>& p) {

F childDst = visitDistance<F,GroupType>(node.getChild(), p);

return std::visit( // note that unary ops mess with their child's distance value

[childDst](const auto& arg) {return sdfUnaryOp<F>(arg, childDst); }, node.getPayload());

}

export template<typename F, typename GroupType>

F visitDistance(const typename GroupType::DomainOp& node, const ivec::vec<F, 3>& p) {

ivec::vec<F, 3> pnt = std::visit( // wheras domain ops mess with the given test-point p

[p](const auto& arg) {return sdfDomainOp<F>(arg, p); }, node.getPayload());

return visitDistance<F, GroupType>(node.getChild(), pnt);

}

// IMPORTANT: DEFINERS OF VISITORS that use overload resolution

// must have the most generic version defined last - (or of course just declare all of them first before defining any)

export template<typename F, typename GroupType>

F visitDistance(const typename GroupType::NodeVariant& node, const ivec::vec<F, 3>& p) {

return std::visit(

[&p](const auto& arg) {return visitDistance<F, GroupType>(arg, p); }, node);

}

Thats it! Nice and brief! Lets pick it apart: We’ve got a group of functions, which the compiler discriminates via overload resolution, one for the generic case and one for each of the 4 classes of node. At each point where we dont know which of the alternatives is held at runtime by an std::variant, we use std::visit() which always has just a single lambda with an auto-typed argument! this visit function is effectively taking the place of the v-table that would be in use in a virtual interface scenario - it internally associates keys with the alternatives types it could hold, and at runtime must evaluate that key to figure out the actual type. On the plus side, this is all hidden from us and we can just use a very pleasant auto lambda.

This little pack of code lets us evaluate the distance from a point p to any compound SDF object represented by our tree. The GLSL shader generator visitor follows a similar, simple pattern. Rather than evaluate the distance functions, however, it instead collects strings that define the distance functions in GLSL, and composes a them into the GLSL code that would evaluate them. This snippet is then injected into a simple GLSL host that marches rays through the scene, and renders the results.

Conclusion

Although it was more than a little confusing to make, I think this approach achieved the goals. Although its non-conventional form is I think in conflict with the goal that loose coupling implies - that it be easily changed / maintained. It is is pretty flexible, once you get the hang of it, and it was fun to play around with some new ideas - intentionally keeping functions free, making good use of the power of templates, not to mention the novel (to me) method of rendering shapes via SDF! the technique has a lot of interesting benefits and drawbacks vs. your average array of indices and vertices!

One last thought this experiment left me with - I feel like c++20 modules revitalize the C++ preprocessor, rather than making it obsolete! It is with good reason that #defining all kinds of wild __DANGER_SYMBOLS__ is not in vogue these days, but by keeping them private in each module, I actually think its made them a much more viable option for code preprocessing!

I’ll leave you with a short, underwhelming video of the app in action, and of course all the code is available in full on github.